Almost a decade ago I set up a (short-lived) blog in an attempt to dispel some of the myths surround the whole Uber phenomenon. The rationale of this new blog is similar, although the intended context is a bit wider. However, Uber is still central to many of the fictions surrounding the industry more generally, not to mention the general lack of nuance often relating to such discussion. A couple of online press articles from the last few days provide ample evidence of this.

Both concern an influx of Uber vehicles into Blackpool and Lincoln, two substantial settlements of more than 100,000 people (strictly speaking, Lincoln is a city rather than a town in the title of this post). The basic arguments are nothing new, and similar pieces have appeared in the local press from dozens of locations over the past few years, and often concern so-called ‘cross-border’ working (when vehicles operate in a location other than where they’re licensed) and Wolverhampton-licensed vehicles in particular (which is a sort of Amazon of ‘taxi’ licensing). The arguments for and against this are quite well rehearsed (in the national context, at least) and will be considered in more detail in subsequent pieces. But the purpose of this particular post is to point out some of the more obvious shortcomings and mis/disinformation relating to to the subject, at least as far as the two press articles are concerned.

No point, either, in going through it all with a fine tooth comb. However, for a start the Lincoln article contains the usual jumble of often misleading terms. For example, ‘hackney cab drivers’ is clear enough but, at central government level at least, that is what is termed a ‘taxi’, however the t-word seems to also be used generically in the piece to mean either a hackney or private hire vehicle – Uber vehicles are almost always licensed as the latter. So when the report says ‘every taxi driver licensed in Lincoln has to do a knowledge test to check how well they know the city’, it’s not clear if that means just hackney drivers, or private hire drivers as well. Which is often important in terms of barriers to entry, insofar as that might rationalise Uber licensing private hire drivers in an area with less exacting standards, such as Wolverhampton.

Then there’s the outright incorrect stuff, such as one driver quoted as saying: “If you wanted to start a private hire company here you’d be restricted about how many cars you can have.”

That reads like utter nonsense. But in the unlikely event it’s true, highly unlikely to survived a legal challenge.

The driver also said: “At weekends, [Ubers] just come in from miles around to work here because of the students and the kids.”

Which perhaps points to one misleading myth perpetrated by protectionist local trades – just because drivers are licensed elsewhere and work for the likes of Uber doesn’t automatically mean they’re driving in from miles around – they may well simply be local drivers who prefer to work under the Uber brand and obtain licenses from a cheap and efficient licensing authority like Wolverhampton.

And which is maybe why the equivalent Blackpool article doesn’t even mention the Wolverhampton angle, because established local operators in Blackpool also use Wolverhampton-licensed cars, thus a more obvious example of drivers simply using Wolverhampton City Council for licensing purposes because it’s cheaper and easier. However, the thrust of the piece is outlined in the opening paragraph:

Blackpool South MP Chris Webb used his first Parliamentary question since being elected to highlight concerns over unlicensed taxi drivers picking up passengers in Blackpool.

Leaving aside the misleading use of the t-word in relation to what are almost certainly private hire vehicles, another near-certainly is that the vehicles and drivers are not unlicensed. Which again is why they’re very probably private hire vehicles, and which terminology implies they are licensed. The piece continues:

Chris said in the House of Commons: “Blackpool is experiencing a scourge of unlicensed taxis in our treasured seaside resort. Uber and similar companies who have no operating licence in Blackpool, are allowing passengers to use their unlicensed taxis, uninsured – creating a real public safety risk.”

Again, all that seems highly improbable, and the giveway is possibly in the passage that ‘Uber and similar companies who have no operating licence in Blackpool.’ But it’s axiomatic that operators don’t need a licence in a particular location to offer their services there, hence the whole cross-border working thing. As indeed the earlier Lincoln article states:

City of Lincoln council said that national regulations now mean that all private [hire] vehicles can work without geographical restrictions.

And the Blackpool article further says:

The question arose from meetings Chris has had with cabbies in the constituency who say they are constantly battling against drivers coming into the resort from other towns mainly using digital ride-sharing apps. He said he was told other drivers were travelling “to Blackpool as they see an opportunity to capitalise on our busy summer season.”

Again there’s the stuff about drivers appearing from elsewhere, whereas that’s at least partly about local drivers simply licensing in the likes of Wolverhampton for reasons of cost and convenience. Another clue is the meaningless phrase ‘digital ride-sharing app‘ designed to portray the likes of Uber as a different beast, and which helps cement the ‘unlicensed’ narrative. (While the vacuous term ‘ride-sharing app’ is pretty much ubiquitous in Uber-related reportage, the addition here of the word ‘digital’ isn’t, and is presumably intended simply in terms of embellishment – the phrase becomes slightly tautologous, because by definition an app must be ‘digital’.)

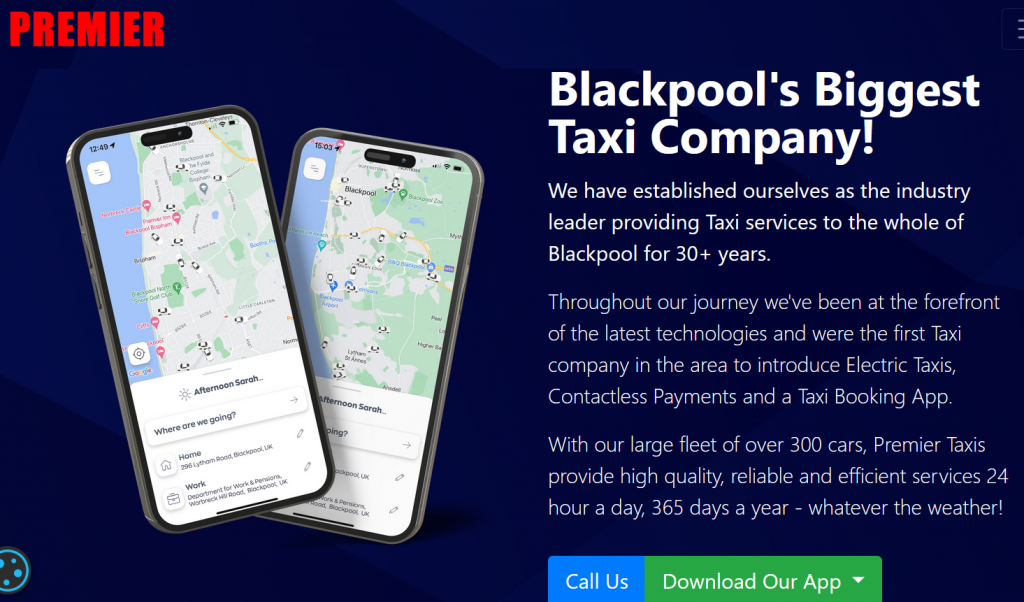

But simply visiting the top two websites (C Cabs and Premier Taxis) in the Google ranking for the Blackpool industry shows an app prominently displayed on their homepages. So what’s Uber’s ‘digital ride-sharing app’ if it’s not simply a version of those used by C Cabs and Premier Taxis?

The article also specifically says this, which of course is the precise opposite of what Lincoln City Council said above:

Operators such as Uber can only work in Blackpool if they have an operating licence from the council, which is currently not in place.

And indeed a 2021 piece also in the Blackpool Gazette and written by the same journalist said:

A change in the law in 2015 allowed private hire drivers, who must be pre-booked, to operate in a different area from where they obtained a licence. (1) (2)

The article winds up with Blackpool South MP Chris Webb saying he’s ‘had meetings with the council’s licensing team and the cabinet member Coun Paula Burdess’. Councillor Burdess wouldn’t be the first member of a licensing committee to be totally clueless about matters that they’re charged with regulating, but paid officials should know the very basic facts about these issues, which is all that is really required in terms of much of the content of the article. (3)

To be fair to Mr Webb, he wouldn’t be the first politician to be spun a line by industry insiders and ‘stakeholders’, and no doubt when his parliamentary question is answered he can then perhaps address the issue from a more realistic angle.

Late to the misinformation party is the BBC News site, which includes this little gem:

Drivers who are not in vehicles licensed in Blackpool can only drop off from their original place where they have a license and cannot pick up in the town.

At best, that sort of stuff arguably reaches little more than the status of taxi rank myth. In a nutshell – and provided the necessary licences are in place – a private hire vehicle can pick up and drop anywhere in the country. Generally speaking, a hackney carriage can do likewise, provided the journey is pre-booked. So there’s a general ‘right to roam’ for both private hire vehicles and hackney carriages. The proviso is that only hackney carriages can undertake public hire engagements (by being hailed in the street, or at a taxi rank), and only in the local authority area in which they’re licensed (although once hired they can convey the passenger to outside the licensing area).

But since these and similar issues have been around for decades now and are effectively settled law, it never ceases to amaze how often this groundhog day of trade issues once again raises its head.

NOTES

(1) Another oft-cited myth is that cross-border working was implemented via the Deregulation Act 2015. In fact this legislation merely facilitated a process that had been going on for some years previously.

(2) The scenarios depicted in the 2021 article and the more recent piece are slightly different in that although both concerned Wolverhampton-licensed vehicles working in Blackpool, the local firm in the earlier report had a Blackpool operator’s licence, and to that extent could also use Blackpool-licensed vehicles. The latest scenario about Uber using Wolverhampton-licensed cars does not involve a Blackpool operator’s licence, and that’s why Uber can’t use Blackpool-licensed vehicles.

(3) No real point finding out precisely what Councillor Burdess’s position is, but she’s presumably some sort of what’s conventionally called a licensing councillor – as befits self-aggrandising local authorities these days, her official profile page states that her job title is: “Cabinet Member for Community Safety, Street Scene and Neighbourhoods.”

Or, as a cynic might suggest, the Cabinet Member for Cluelessness.

(4) The 2021 report ironically involves the two firms above who came out top of a recent Google search. But at that time the clash was about the two established operators, one of which was using Wolverhampton-licensed vehicles (for the reasons stated earlier, essentially) while the other was only using cars licensed by Blackpool Council. Which underlines the point above about Wolverhampton vehicles working cross-border not necessarily being about drivers rolling up from elsewhere in the country. In essence, Uber is little different in terms of licensing and competition fundamentals, but the scale of its operations and ubiquity of its brand means its supposedly unique character is grossly overstated.